Jump to Video

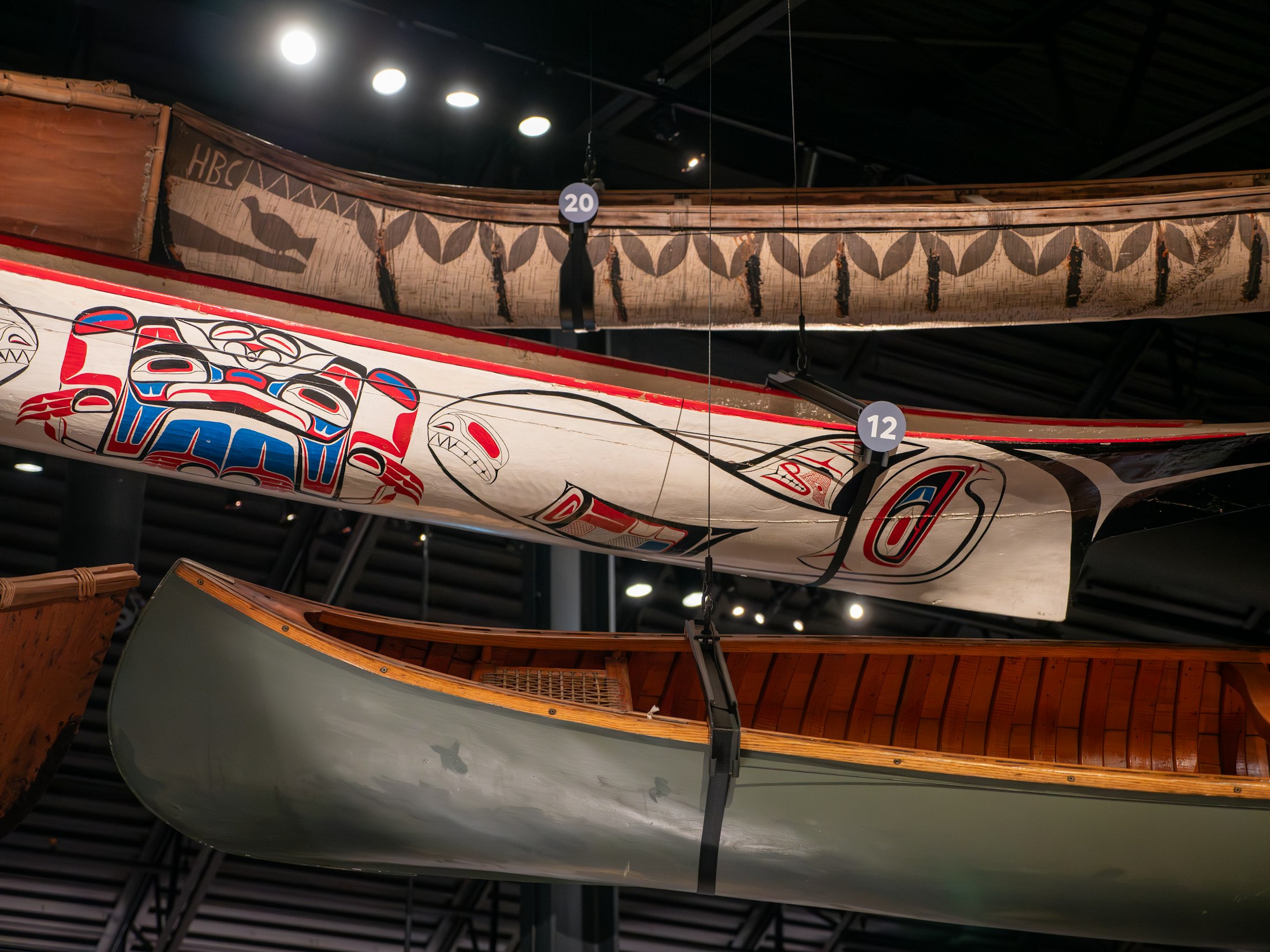

“Canoes as far as the eye can see” might be an exaggeration, but only slightly. The Canadian Canoe Museum’s expansive new collection hall is home to over 500 canoes, carefully arranged from floor to ceiling in a climate-controlled storage space. Turn down one aisle and you might see a selection of traditional Welsh coracles—small fishing boats that look like the canoe’s distant cousin—across from Greenlandic skin-on-frame kayaks. Stroll up another, and you’ll walk past craft once owned by Canadian luminaries like Gordon Lightfoot and Farley Mowat. Visit a third and you’ll find feats of experimental engineering, including concrete canoes. All this before visiting the museum’s main exhibition area, where over 100 more canoes await curious visitors.

The Museum has been a landmark Peterborough attraction since 1997, but moving to a new location at 2077 Ashburnham Drive has given it the space for a more sophisticated showcase. The collection hall, once hidden out of view, can be visited during tours or viewed through sleek 23-foot glass windows. The bright, airy atrium is now home to a branch of the Silver Bean Café, where visitors can gather without even visiting the exhibits. Better still, waterfront access to Little Lake means programs regularly extend beyond the building itself.

Speaking to executive director Carolyn Hyslop and curator Jeremy Ward, the excitement about the museum’s expanded prospects is palpable. “Being on the water has been our aspiration for as long as I’ve been involved with the museum,” Hyslop says—no small accomplishment, considering she’s been working towards it for over 20 years.

Ward jokes his favourite thing about the new facility is “everything,” but agrees being on the water is a game-changer. “For instance, teaching a canoe paddle-making course,” he says. “We’ve been doing this for decades… But now at the end of that process we can tell them, the staff have our Kevlar canoes all lined up for you. Now that you’ve finished sanding it, why don’t you take your brand-new paddle for a spin on the lake?”

Establishing the new facility wasn’t without its hurdles, but the gambit has paid off with glowing reviews from visitors. Early in the year Museum was paid a high honour when it was named in the New York Times feature “52 Places to Go in 2025.” Seeing the region appear alongside international treasures like the Galapagos Islands and the Dolomite Mountains is a major honour, but a deserved one for the world’s largest collection of canoes.

Quantity alone, of course, isn’t the secret to the museum’s success. “What we hear the most is, I can’t believe the incredible stories. It’s about the stories,” says Ward. “I think people are really surprised at how these stories resonate with them, much more than they might’ve thought from a what they perceive just to be a watercraft museum.”

For instance, shallow grooves in the ribs of a fur traders’ canoe give a clue about the heavy-duty boots worn by its paddlers, and hint at that craft’s many arduous voyages. Yet if that detail seems easy to miss, Hyslop points out there are many tales told directly by modern canoeists and canoe builders. “It’s not stuck in the past,” she says. “It’s not a historical review of paddled watercraft in Canada. It is very much about the people, and the places, and these watercraft today.”

One way the Museum bridges the gap between past and present is by offering all principal texts in the local dialect of Anishnaabemowin. The City of Peterborough sits within Michi Saagiig and Williams Treaties territory, and the Museum is home to many Indigenous artifacts from both at home and further afield. Respect for language is therefore essential to the Museum’s approach. It strives to present both an accurate historical perspective, as well as represent the knowledge and skill found in communities today. The main exhibit’s video of a contemporary builder assembling a birchbark canoe is one example.

“We care for Indigenous watercraft that come from home communities, and to do that we need to have good relationships,” says Hyslop simply. “We wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for good relations.”

In fact, Ward adds, the Museum’s location is intimately connected to the region’s Indigenous history. “This is a really important canoe route that stretches back millennia. All of the people who’ve paddled through here, this being Michi Saagiig territory, have influenced everything throughout the museum experience here,” he says. “That’s really an important resonance for the guest experience.”

He notes that many places where major rivers meet could make a similar claim, but Peterborough’s later history as a hub of canoe manufacturing sealed the deal. With so many facets and connections to the history, the potential for future exhibitions and research is practically limitless. “Frankly, we could do new exhibitions for a hundred years without acquiring another canoe,” says Ward. “There’s just so much richness to work with here. And our growing network coast to coast and beyond now really enables us to work with people with connections to these watercraft.”

With that in mind, Hyslop and Ward are constantly exploring new possibilities. Four builders-in-residence are scheduled to visit in 2025, covering cedar canvas canoes, birchbark canoes, traditional etching, and Inuit kayaks. This specialized programming will complement the Museum’s other projects, including youth programming, a speaker series, virtual outreach, and a new exhibit opening in June centred around Temagami First Nation.

With literally thousands of years of history within its walls, and an ever-expanding approach to living history, it’s impossible to grasp the Museum’s offering in a single visit. For some, it may be the launching point for their first experience on the water; for others, it may be a highlight of their trip down the Trent-Severn Waterway. Through a workshop, it might be a way to engage with the process of working with their hands. What unifies each experience is the respect for a flexible, infinitely variable masterpiece of design, and the human stories that emerge whenever we spend time on the land or on the water.

Visit canoemuseum.ca to learn more